I began photographing with the pinhole camera a number of years ago in a desire to slow down as a photographer. I wanted to trade, at least occasionally, the precision and instant gratification of digital photography for something that required me to spend more time with my subjects, to immerse myself in each and every frame.

What I did not anticipate is that stripping back to this most basic way of shooting would somehow yield images that also seemed more elemental, that brought me back to an earlier, uncluttered, more innocent way of seeing.

The pinhole camera is the most rudimentary camera one can photograph with; it has no lens, no shutter and no viewfinder. The light is focused through a tiny pinhole aperture, which is then captured with the image directly onto sheet film.

Exposure times with the pinhole camera can vary greatly depending on the light source. Even on the sunniest of days exposures will be 4-10 seconds long – in the shade exposures are measured in minutes. During these long exposures the wind blows, clouds move, rivers flow, the earth rotates….creating a dreamy, soft-focus world where the “distractions of detail” are softened and the very essence of the subject comes through.

I soon realized these simple cameras, despite having no lens, had an uncanny and remarkable capability of depicting and rendering landscapes. The cameras somehow looked deeper into the subjects and I actually found myself experiencing these landscapes and the photographic process in a more profound way.

After working with the cameras over time, the handicap of having no viewfinder to compose with actually became a blessing. When photographing with the pinhole camera you take-in, you experience the entire landscape at once, composing the images in your mind then physically walking into the compositions and setting down the tripod – the process is intimate, unhurried and deliberate.

The rudimentary mechanics of the pinhole camera, it’s honest and unadulterated rendering of the subject and the inherently soft and dreamy images it captures seemed a perfect fit for visualizing this epoch.

Adding dimension to the imagery the tiny pinhole aperture would require long exposure times – the camera would have to linger on these subjects. Reflected light from the battlefield landscapes would slowly creep into the camera; recording not just the subject but somehow the “atmosphere” – the “feeling” of that moment in the landscape.

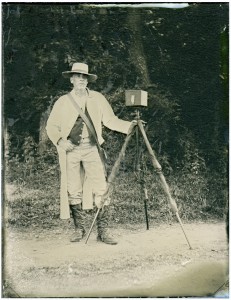

The pinhole camera does captures a stillness and the quiet beauty that continues to haunt these historic battlefields to this day. These wood-box pinhole cameras have also helped me blend in on the reenactment battlefield where I have taken on the guise of a 19th century photographer. Embedding with the “troops”, becoming a reenactor myself, has given me the opportunity see these commemorative events from the “soldiers’ perspective.”

Echoing the sentiments found in period letters and soldiers’ journals about the visual experience of 19th century combat, the pinhole camera captures the battle reenactments in an authentically “dreamlike way” – the long and soft time exposures highlighting the feeling of battle. The blurred and wistful pinhole images are able to capture the universality of anonymity; reenactors emerge not merely as impersonators, but as “every soldier.”

Text by Michael Falco